Where does plant-based meat fit in the ultra-processed foods narrative?

Why more nuance is needed to help drive meaningful change towards a healthier, more sustainable food system.

Questo articolo è disponibile anche in italiano.

Este artículo también está disponible en español.

04 August 2025

The recently published UPDATE trial has once more attracted headlines on the topic of ultra-processed foods (UPF). The largest and most robust study on UPF to date, it designed two diets that met the UK healthy eating guidelines – one primarily minimally processed and one primarily ultra-processed – doubled them in size so people could eat as much as they wanted, and compared the outcomes when two groups of people with BMIs in the overweight category, recruited from the staff at UCL university hospital, followed them.

The results were interesting: while those on the minimally processed arm lost weight as expected, counter to the expectations of the authors, those on the UPF diet did too, albeit to a lesser extent. Indeed, for the other outcomes measured the picture was mixed: when looking at adherance, those following the UPF diet were better at sticking to the diet, and every single one of the people who dropped out during the trial (14%) did so while on the minimally processed diet. There were also differences in biomarkers, with the UPF arm performing better in terms of reductions in LDL (bad) cholesterol, and the minimally processed arm performing better in terms of triglycerides. Those on the UPF arm also ate more fibre and less red meat, while those on the minimally processed arm ate more vegetables.

While the trial diets did not contain plant-based meat (although plant-based milk was included), these findings once more highlight the complexity of processing as a topic, and underscore the need for more specificity and nuance in this currently very polarised conversation.

Based on the differences in findings, it doesn’t make sense to conclude that something fundamental about UPF was behind the better performance of the UPF diet on LDL cholesterol, nor that something fundamental about the minimally processed diet was behind the reduced adherence. In all likelihood, it suggests that each diet had strengths and weaknesses, and by taking the good parts from each you could probably create a diet not defined by processing that would perform better than either.

If we assume there is only limited bandwidth that each person has to improve their diet, it follows that the most effective strategies to improve access to healthy diets will target the most pressing areas of mismatch between intake and guidance. Namely, increasing intake of those foods people often don’t eat enough of like fruit, vegetables, legumes and wholegrains, and supporting reductions in intake of those foods with the largest increased risk associations like sugary drinks and processed meat.

What does this have to do with plant-based meat?

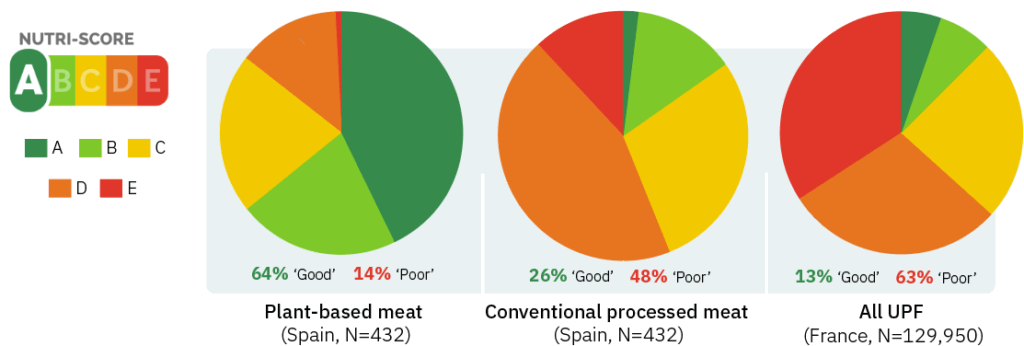

This brings us to where plant-based meat fits within the ultra-processed food conversation: it generally has a good nutritional profile, and offers a simple swap for conventional processed meat which does not. However, it is also often considered an ultra-processed food.

The subject of ultra-processing is incredibly complex and, particularly for the general public, often confusing. While most of the foods in the UPF category are undoubtedly unhealthy in excess, their categorisation is not based on nutritional criteria, and some of them have good nutritional profiles.

This broadly stems from the fact that the system that gave us the term ultra-processed foods – a classification system called Nova – was developed to look at eating patterns on the population level and explore the food system shifts that have led to growing rates of chronic disease and diet-related ill health in several countries. This research suggests that a shift away from traditional home-cooked meals and towards convenient, cheap, mass-produced options (characterised as UPF) has played a role in driving these negative health outcomes.

But this can’t explain the whole story – after all, a home-made cake may not be ultra-processed but it is not advisable to eat every day. For the most part, foods falling into the UPF category also have poor nutritional profiles, they are also quick to buy and ready to eat, a much lower effort barrier to eating too much of them than if you had to make them from scratch. The foods making up the bulk of high-UPF diets in research tend to be high in salt, fat and sugar, and low in fibre – such as hot dogs, fizzy drinks, milkshakes, salty snacks, cakes and pastries. It therefore makes sense that people with the highest proportion of their diets coming from these foods generally have worse outcomes, particularly when considering that the UPF group by definition does not contain any fresh fruit and vegetables – an important part of any healthy balanced diet.

However, not all UPFs have a poor nutrient profile. Plant-based meat is a key example – generally being low in saturated fat and sugar, high in protein and a source of fibre.

While the conversation around processing has become front-page news, most people don’t yet have a good understanding of plant-based meat’s nutritional profile or how it is made. As a result, it is easy to see why the conversation around processing has led to confusion about the health profile of plant-based meat.

Healthcare professionals have a key role in helping support the public in making healthier choices, and helping them to find personalised approaches that fit with their individual needs and preferences. Our new guide, developed in collaboration with the Physicians Association for Nutrition International, aims to shine a light on the nuances and underlying evidence surrounding the complex topic of plant-based meat and the ultra-processing debate.

How plant-based meat can support healthier, more sustainable diets

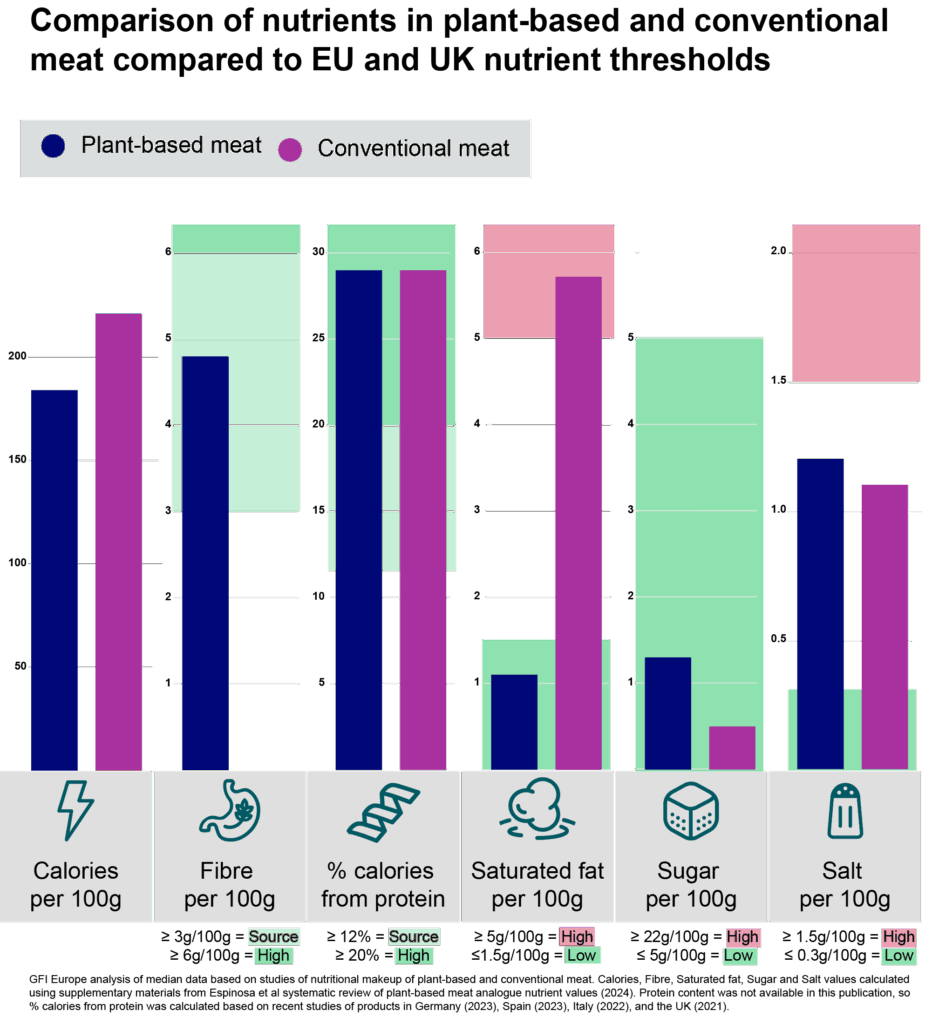

Many European countries’ national dietary guidelines recommend the limiting of processed meat consumption, but the constant time pressures of modern lifestyles, coupled with an abundance of cheap, tasty products like bacon and ham, can make it hard to keep intake within recommended limits. Plant-based meat offers a simple swap that is low in saturated fat (while processed meat is generally high) and offers a source of fibre (while conventional meat has none) while offering similar levels of protein.

The evidence we have so far on plant-based meat is still at a relatively early stage, but what we do know is promising:

- It is well established that lower intakes of saturated fat are associated with reduced cardiovascular disease risk, and higher intakes of fibre are associated with several health benefits, including better weight management.

- The results of trials to date on the impact of swapping conventional meat with plant-based meat show benefits in line with these features of its nutritional profile – with the most consistent differences observed being reduction of LDL cholesterol, and modest weight loss in those above the recommended healthy weight. This is based on a systematic review and meta analysis of 7 randomised controlled trials comprising 369 adults.

- These findings are very different from studies looking at the impacts of diets high in UPF at the population level, which tend to find that high consumption of foods within the UPF category as a whole is associated with higher rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease.

In addition to this, there are several reasons why it is unlikely that available observational UPF research can be usefully applied to plant-based meat:

- Plant-based meat has a very different nutritional profile from the majority of foods in the UPF category. In particular, it is low in sugar and saturated fat, a source of fibre and high in protein.

- Plant-based meat makes up a vanishingly small percentage of calories eaten in the datasets used in most UPF research.

- The long-term nature of observational UPF studies means that the food diaries they are based on are often over 10 years old, use food frequency questionnaires that do not give enough information for researchers to separate plant-based meat from more traditional foods like tofu, and date from before most modern plant-based meat options existed.

- Only a few randomised controlled trials have been published to date on the impacts of UPF, the largest and most robust of which being the UPDATE trial in 55 overweight hospital staff. However, none of these trials included plant-based meat in their diet plans.

- The most consistent finding across these trials was differences in weight between UPF and minimally processed arms: minimally processed diets were consistently associated with a lower weight than their conventional counterparts, although calorie consumption was also higher in all UPF compared to minimally processed diets too.

- These findings are notably at odds with the results of research into plant-based meat specifically: a systematic review and meta analysis of randomised controlled trials exploring the impact of replacing conventional meat with plant-based found people considered overweight generally saw greater reductions in bodyweight on the plant-based arm.

As such, while the evidence does suggest that people who get the largest proportion of their diet from UPFs generally have worse health outcomes, it seems unlikely that this research can tell us much about plant-based meat specifically – particularly when it is eaten as part of a healthy balanced diet alongside a diverse range of fruit, vegetables legumes and wholegrains.

The best diet is one you can stick to

In broad brush strokes, there is no single pathway to a healthy lifestyle, and different approaches clearly work better for different kinds of people. A key opportunity area for plant-based meat lies in its ease of adoption and ability to help reduce the current overconsumption of conventional processed meat, a subgroup of UPF with particularly strong associations with negative health outcomes when eaten in excess, observed in studies from Europe, the US and South Korea.

Plant-based meat is sometimes viewed as a niche food for those already following plant-rich diets like vegetarians, but its primary potential for public health lies in broader mainstream adoption. It has the largest potential for the many people who enjoy meaty meals, eat less fibre and more processed meat than recommended, and don’t want to completely overhaul their diets, preferring options that fit within their existing daily routines and meals. Increased availability of tasty, affordable, nutritious plant-based meat designed to appeal to these people could help improve diet quality and make plant-based foods more approachable and easier to prepare – currently a barrier to adoption for many people.

A study exploring the patterns in diet change of the ‘champion households’ for diet sustainability in the UK found two distinct patterns amongst the groups who most effectively reduced the greenhouse gas emissions of their diets. All of those successfully reducing emissions significantly reduced their intake of meat, but some switched meat for dairy, and some increased their intake of plant-based foods.

While both groups reduced the carbon footprint of their diet, only the plant-based increasing group saw co-benefits with health. The meat to dairy group overall saw a decline in diet quality: there was no increase in consumption of vegetables or legumes, while foods that were increased varied significantly in nutritional profile. Dairy products saw by far the largest increases, followed by smaller increases in plant-based milk and fruit. Increases were also seen convenience food groups commonly associated with the UPF group: desserts, snacks and bakery.

Meanwhile, those taking the plant-based increaser approach reduced the environmental impact of their diets while also seeing diet quality improvements. Vegetables, plant-based milk and fruit saw the largest increases in intake, followed by plant-based meat, legumes, nuts and seeds. In this group, unlike the meat to dairy group, common energy-dense foods such as confectionary, desserts, pre prepared foods and bakery also fell.

This suggests that adoption of plant-based meat is generally more closely associated with the positive dietary shifts towards healthier and more sustainable diets than it is to other foods in the UPF group, and far from reinforcing the ‘status quo’ as is often suggested, they could make plant-rich diets more generally accessible and easier to stick to.

Our analysis of European sales data in six European countries also speaks to this: despite being a more recent invention and often more expensive, plant-based meat saw considerably higher sales volumes than other high-protein plant-based foods across all European countries studied. This suggests greater efforts to further improve taste and bring down prices could lead to wider mainstream uptake, and support shifts towards healthier more sustainable diets.

In this context, a variety of complementary strategies are likely needed to support lasting shifts towards healthier, more sustainable diets. Within this, there are important roles to play both for plant-based meat and for broader initiatives to significantly expand uptake of fresh vegetables, fruits, legumes and wholegrains.

The role of fortified, high-protein plant-based foods in safeguarding food security

We know that in the shift towards healthier, more sustainable diets, we urgently need to eat more plant-based foods. But it is also important to remember that, at present, for most of the European population animal-based foods are currently a primary source of several important nutrients like B12, zinc, iodine, calcium and long-chain omega 3s.

Several of these nutrients are not inherent to animal-based foods – and their presence and consistency are often the result of fortification added to animal feed and farming practices that boost the content of these nutrients. One example is iodine. Not naturally found in dairy in high quantities, iodine is routinely added to cow feed and is also used as the base of some disinfectants used in milking, which consequently provide iodine content commonly found in dairy products.

B12 – often associated with animal products – is another example. B12 is only made by certain types of bacteria, and neither plants, animals nor fungi can naturally produce it. These other organisms must therefore get it either from diet or, in the case of ruminant animals, from symbiotic relationships with gut bacteria. Fortified animal feed and veterinary supplementation are therefore the original source of much B12 in animal-based foods eaten in Europe, particularly in the case of the meat and eggs from birds and non-ruminants. In the wild, concentrations can also vary significantly between ruminant animals on the basis of soil composition, so consistency is ensured in farmed ruminants through the routine provision of supplementation with cobalt to support these gut bacteria or direct supplementation with B12.

In contrast, consistency of fortification in analogous plant-based foods is limited, and needs to be improved.

While fresh vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts and wholegrains all contain a wide variety of health-promoting nutrients, plant foods also often contain compounds that make certain nutrients more difficult to digest than equivalents from animal or fungi-based foods – sometimes called ‘antinutrients’. This is true for both micronutrients like calcium, zinc and iron, and also for protein. While these needs can usually be met by eating a larger volume of food, or by supplementing or planning diets more carefully, fortified plant-based foods with better bioavailability may make it easier for people less knowledgeable about nutrition, or people less able to eat larger volumes (eg older people) to get everything they need from their diet.

Certain processing approaches show promise in overcoming these challenges, and this is a key area where more research is needed. The distinctive nutritional profile of plant-based meat, coupled with the scope for improved bioavailability of macro and micronutrients, could offer new approaches to support people with specific nutritional needs for nutrient dense, high protein, high fibre foods that are also low in saturated fat. Populations for whom these considerations could be particularly important are athletes, older people, and those on GLP-1 agonists. These avenues of research should be explored.

Besides the environmental challenges linked with current over-consumption of animal-sourced foods, our current over-reliance on meat and dairy for key nutrients at the population level also presents risks for food security. The ongoing bird-flu epidemic, and resulting price increases and shortages in the egg supply in the United States, is a primary example of this, and a strong reminder of the importance of protein diversification to safeguard affordable access to nutritious diets. As the growing impacts of climate change on agriculture put increasing pressure on our food systems, the higher resource intensity of animal source foods make them susceptible to supply shocks and price increases. Nutrient-dense plant-based options that are tasty and affordable could therefore play a central role in a more resilient food system.

Without a nuanced approach to processing, however, these potential advantages may be neglected and the considerable opportunities offered by plant-based meat and other high-protein, fortified plant-based foods missed.

The importance of collaboration in building a more sustainable, secure and just food system

With the pressing need to diversify our protein supply for both public and planetary health, a diverse range of strategies is likely required to support the necessary increase in consumption of plant-based foods. Public support for tasty, affordable, nutritious plant-based meat and initiatives to expand uptake of fresh vegetables, fruit, legumes and wholegrains are two such strategies, each likely with differing appeal and importance for different demographic groups.

On this basis, there are many areas where proponents of the Nova framework and of protein diversification could work together to build a healthier, more sustainable food system. Achieving this requires greater understanding and acceptance of the nutritional benefits of nutritionally optimised plant-based meat, alongside more nuance in the UPF discourse.

Check out the full guide, developed in collaboration with the Physician’s Association for Nutrition, to learn more about this topic, and explore our summaries, available in English, French, German, Italian and Spanish.