Meet the researcher: Using precision fermentation to unlock next-generation foods with Maija Greis

A background in food science convinced Dr Maija Greis that precision fermentation was crucial to finding the missing ingredient in developing animal-free foods with the authentic taste and texture of conventional meat and dairy.

8 December 2025

Name: Dr Maija Greis

Job title: Postdoctoral researcher

Organisation: KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Alternative protein specialism: Precision fermentation

A background in food science convinced Dr Maija Greis that precision fermentation was crucial to finding the missing ingredient in developing animal-free foods with the authentic taste and texture of conventional meat and dairy.

The researcher is working on a project at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm aiming to improve some of the characteristics of beta-lactoglobulin, the most abundant whey protein in cow’s milk.

This protein is one of the key building blocks of dairy, and although lovers of whipped cream and yoghurt may never have heard of it, its ability to gel and foam is crucial to the trademark structure and mouthfeel of these foods.

Precision fermentation is a process that enables scientists to provide organisms like yeast with the instructions needed to produce a wide range of ingredients, much like traditional fermentation uses microorganisms to convert sugars into alcohol.

Using their knowledge of beta-lactoglobulin, Maija’s team is using the technique to provide specific biological instructions to the microorganism, enabling it to produce protein variants that can perform functions such as foaming and gelling even more effectively. By modifying the protein’s sequence, they also aim to eventually improve its nutritional properties.

“Precision fermentation acts as the perfect tool for protein design,” she said. “We’re not just trying to make proteins identical to those that we find in nature, but ones that are better for us, for the planet and for developing delicious food products.”

This ability to create animal-free, functional ingredients, she believes, is where precision fermentation has the potential to be a game changer.

Precision fermentation for tastier plant-based foods

“We are interested in how these ingredients can be used to make plant-based products better in the future,” she said. “We will need to explore how they perform in different applications such as plant-based meat and yoghurts.”

Working on plant-based foods earlier in her career led Maija to see there was a missing piece of the taste parity jigsaw – one that precision fermentation might be able to fill.

After working on product development with Finnish dairy company Valio, which had recently introduced plant-based products, she completed a PhD at the University of Helsinki, collaborating with the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the United States. There, she investigated consumer responses to the texture and taste of oat-based yoghurts.

She said: “One of the main results was that it’s difficult to achieve a truly creamy mouthfeel with only plant-based ingredients, because their properties are so different to dairy ingredients.

“We also found that young consumers were more willing to sacrifice taste properties, but most people think that these sensory properties are not there yet. It’s difficult for a lot of consumers to choose these products over dairy-based yoghurt.”

She went on to work for the Berlin startup Perfeggt but, still convinced that plant-based products lacked a key element needed to meet people’s expectations, decided to put her expertise to work alongside those specialising in the science of microorganisms.

Applying tools recognised by the Nobel Prize

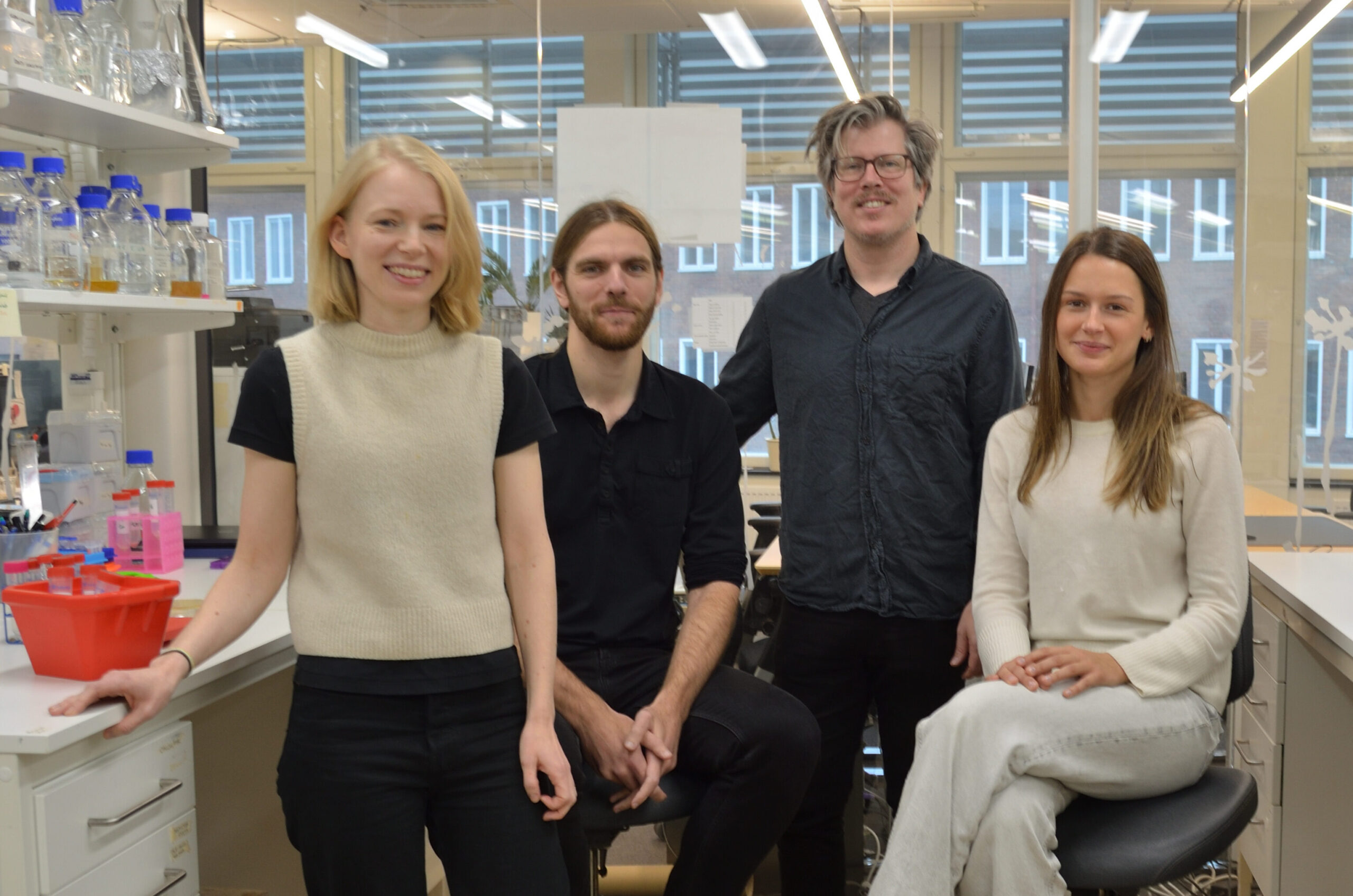

Collaboration and teamwork are central to her work at KTH’s Hudson Lab, where she works closely with PhD researcher Ulysse Castet, who creates new proteins and builds the computational systems needed to generate them.

His work employs a similar approach to that which won the 2024 Nobel Prize for chemistry, in which laureates Demis Hassabis and John Jumper were recognised for using deep-learning computer models to predict the structure of proteins, along with David Baker for learning how to create entirely new proteins.

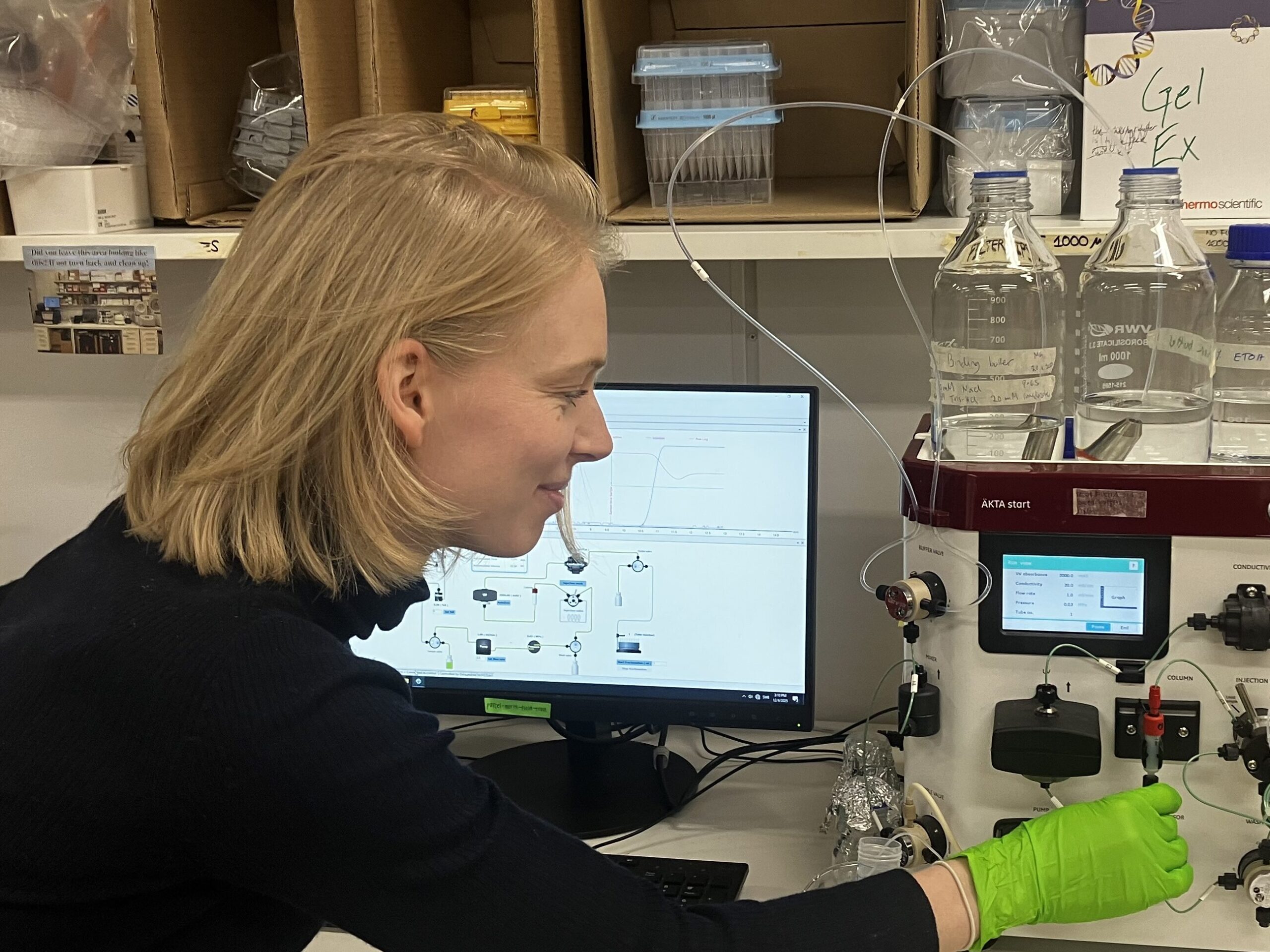

Ulysse applies this technology to developing better food ingredients, generating new protein designs which Maija then tests in the lab. Meanwhile, research engineer Oliwia Bancerz Aleksiejczuk leads much of the genetic preparation, ensuring that each protein variant’s instructions are assembled and transferred into the micro-organisms that will produce them – one of several essential steps in the process.

“Working on protein engineering and precision fermentation is extremely challenging but very exciting,” she said. “The more you learn, the more you want to learn, and you see food science in a different way — full of new possibilities.

“This feels like a very exciting opportunity, and I think we will see a lot of food ingredients coming out of protein engineering and precision fermentation.”

Despite the steep learning curve, Maija believes that her experience demonstrates it is possible for food scientists to make a significant contribution to protein design and precision fermentation research.

“We need people from different backgrounds to make alternative proteins work,” she said. “I would encourage more people to make this step.”

Are you interested in getting involved in the science of plant-based food, cultivated meat and fermentation? Take a look at our resources or check out our science page.

If you’re a researcher:

- To find funding opportunities, check out our research funding database for grants from across the sector, and our research grants for funding available from GFI.

- Explore our in-depth analyses of the most pressing knowledge gaps in alternative protein research.

- Subscribe to the alternative protein researcher directory to find potential collaborators or supervisors in the field.

- Look out for monthly science seminars run through our GFIdeas community.

If you’re a student:

- Join the Alt Protein Project – the global student movement dedicated to turning universities into engines for alternative protein education, research, and innovation.

- Find educational courses around the globe through our database.

- Sign up for our free online course introducing the science of sustainable proteins, explore our resource guide explaining what is available to students or newcomers to the space, and check out our careers board for the latest job opportunities in this emerging field.