Scale-up series part 5: No offtake, no scale

Breaking the chicken-egg demand problem is critical to scale up alternative proteins. What lessons can we learn from other industries on how creative offtake strategies, like pre-orders, conditional contracts, and public procurement, can break the cycle of stalled investment?

19 November 2025

The demand risk dilemma

Alternative proteins face a classic chicken-and-egg problem: they need scale to lower costs, but they can’t lower costs until they scale. Scaling requires capital, but investors and lenders are reluctant to fund large-scale production facilities without clear demand signals from buyers. Buyers, meanwhile, are reluctant to commit to long-term offtake agreements for alternative protein products that still carry risks around price, performance, and reliable supply.

The result is a commitment standoff: buyers wait for lower prices, and investors wait for buyers to commit to offtake. With no one willing to move first, capital stalls, and scaling doesn’t happen.

Breaking this cycle means confronting the core challenge: who takes the demand risk. And that’s where creative offtake strategies come in—mechanisms that reduce risk for early buyers, send strong signals to investors, and unlock the capital needed to build.

The power of offtake

Offtake agreements are contracts that guarantee future purchases of a product, and they have fueled the rise of many capital-intensive industries that require significant investment to reach economies of scale. Offtake contracts provide certainty that end products will be sold, and this guaranteed revenue reduces investment risk. While not every sector needs formal offtake commitments, such as instances where there is steady, predictable demand or for high-margin products, offtake is often essential in low-margin, volatile, or emerging industries.

Take solar. Today, solar is the cheapest source of electricity in many regions, with prices falling by 90% over the past decade. But it started as an expensive, niche technology. From the 1950s, early markets like satellites, oil rigs, telecom towers, and off-grid homes paid above-market rates for solar, sustaining the industry when it was still in its infancy. The real breakthrough came in the 2000s, when some governments introduced feed-in tariffs (guaranteed payments for solar power that were backed by government policy) and utilities signed Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). These offtake commitments gave solar developers the financial security to build at scale, which in turn drove costs down dramatically. Solar’s success wasn’t just about better technology—it was about buyers committing early.

Why offtake is harder for alternative proteins

Alternative proteins are more complex. Electricity is a commodity—electrons are electrons, and consumers don’t care where their electricity comes from as long as it’s cheap and reliable. Food, on the other hand, is deeply differentiated. For example, precision fermentation egg protein may behave differently from its animal counterpart depending on the application – it might whip well enough for a cake but not bind effectively for a pasta dough. This creates functional uncertainty and performance risk for buyers who would otherwise rely on animal eggs, where functionality is well understood across these uses. The market structure of food adds another layer of complexity: unlike energy or mining, which rely on a few centralised offtakers, food ingredients often move through “merchant offtake”, with dozens or hundreds of buyers each taking small volumes. That makes it harder to land the anchor commitments needed to justify investment.

No one wants to move first, but someone has to. Without early adopters willing to take the initial risk, alternative proteins will struggle to scale. Breaking the cycle means rethinking what offtake can look like, and finding ways to make it work in food.

Getting to offtake solutions for alternative proteins

Direct offtake solutions

Solutions that are focused on direct engagement and creative contracts with buyers and strategic partners to build early buy-in and commitment for your alternative protein business.

1. Follow the signs of scarcity

Buyers are more likely to act when they anticipate disruption. In 2023, Meiji signed a binding multi-year offtake agreement with cellular agriculture startup California Cultured to secure cell-based cocoa even before it had achieved regulatory approval or scaled supply. This move was made on the back of increasing volatility in the traditional cocoa supply caused by several factors including climate change and new policies aimed at curbing deforestation.

Buyers move when they see scarcity on the horizon, and cocoa will be the first of many. The ongoing egg shortage caused by avian flu and rising input costs is another example of mounting fragility in animal protein supply chains. Alternative protein producers should look for these pressure points, as they create windows of opportunity for you to secure early commitments from buyers who are forced to act when they face supply risks and price instability.

2. Nurture strategic partners for long-term offtake

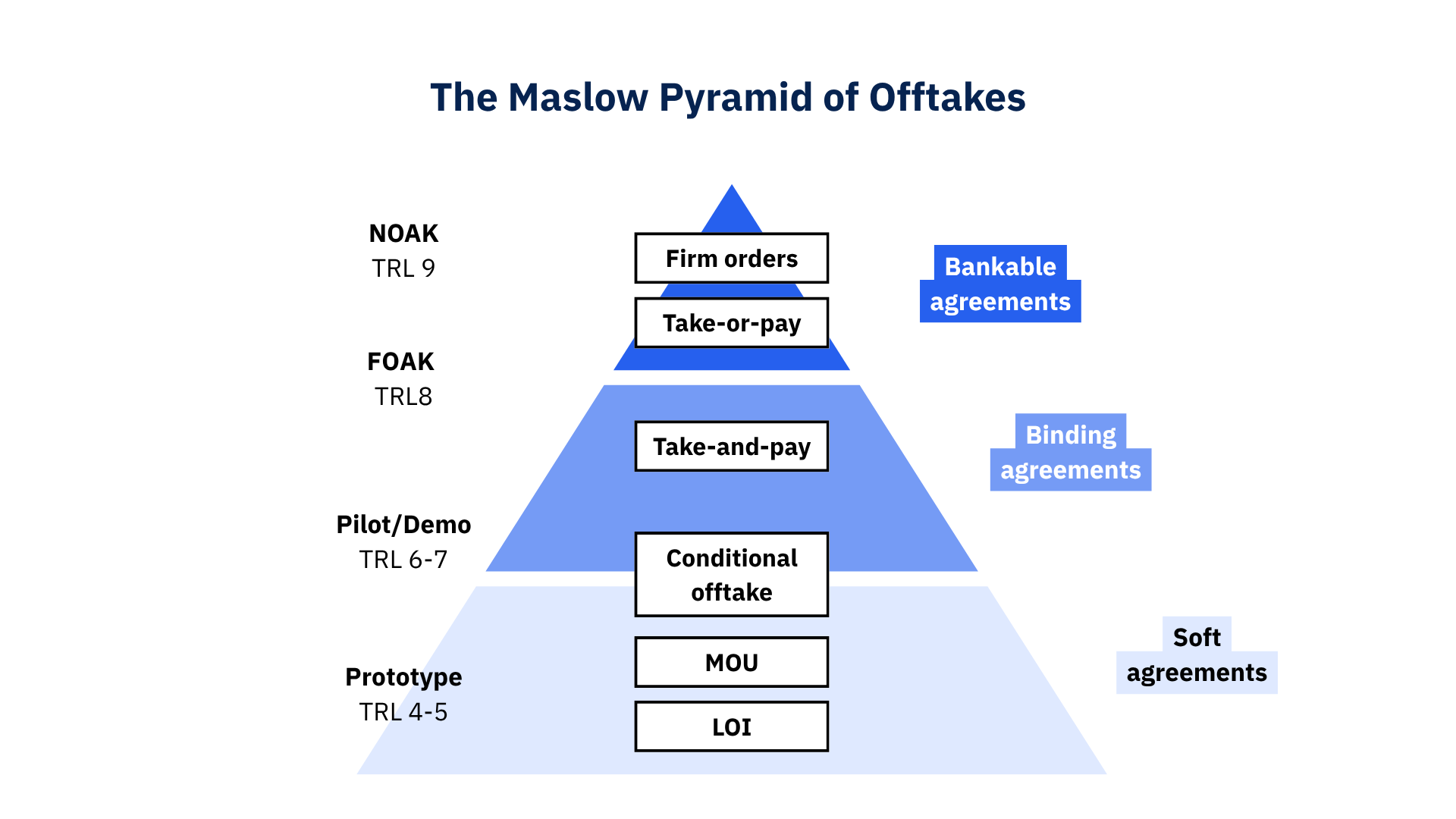

Strategic partners can evolve into anchor customers for a future scaled alternative protein business. The Maslow Pyramid of Offtakes by the climate-focused venture capital firm Extantia offers a useful framework for startups to think about how you can move buyers from soft signals like letters of intent (LOIs) or memorandums of understanding (MOUs), through to binding, long-term offtake contracts. Early engagement or investment from companies who are well-positioned to be future end customers of your business allows corporate partners to gain early insights and confidence in the technology, and provides startups with benefits well beyond financial backing: customer validation, insight on technical specifications for scaled procurement, and your future potential anchor customers.

It’s also crucial for alternative protein startups to creatively consider different categories of demand and potential buyers. For instance, channel partners who resell ingredients or products bring extensive customer relationships and expertise beyond the reach of most startups. Imagine a dairy processor with processing capabilities but no ability to scale animal-based dairy volumes, who could have a compelling business case for being a value-added processor and reseller of fermentation-derived dairy ingredients. An example of a type of channel partnership is Cargill and biomass fermentation startup ENOUGH. In this collaboration, ENOUGH’s facility is co-located with a Cargill facility which provides low-cost feedstock, and Cargill plays a role as a reseller, facilitating the integration of ENOUGH’s “ABUNDA” mycoprotein ingredient into various products and supply chains where Cargill already has deep customer relationships and expertise.

When it comes to securing offtake, alternative protein startups should aim to secure more commitments than needed; a strategy of “over-collateralisation.” This approach mitigates risk by preparing for some commitments not materialising. It is especially important if you are relying on soft commitments without binding contracts, but is still needed with hard commitments, as if large companies breach take-or-pay contracts, startups often have limited recourse. When it comes to offtake, a risk-averse mindset is the right one.

3. Use conditional procurement to reduce buyer risk

Buyers often hesitate when costs, performance, or regulatory outcomes are uncertain. Conditional procurement agreements allow buyers to commit under specific terms—such as meeting targets for price, taste, or regulatory approval—tailored to their requirements. If your alternative protein startup offers terms like preferential pricing in exchange for volume commitments that are triggered once certain conditions like price or performance criteria are met, gradual volume ramp-ups, or exit clauses tied to technical benchmarks, you can ease and incentivise buyers into early engagement without requiring a full offtake commitment upfront.

By shifting your buyers from a high-risk contract to a low-risk option with upside, these structures make it easier for them to engage early, laying the foundations for deeper commitments in future.

4. Pre-order agreements

Pre-order agreements are a creative offtake mechanism that have been used in other emerging sectors to demonstrate a market pull for early technologies before reaching full-scale production. Inspired by Tesla’s go-to-market playbook, the climate tech company Reverion used pre-orders to navigate the funding “valley of death”, validating real buyer interest while still in the process of tech development.

Pre-orders work by asking your buyers to commit to buying a future product, but only with a small, fully refundable deposit. This small upfront payment provides buyers with a low-risk entry point to secure future access to a product (which they can back out of at any time), while the pre-order arrangement gives startups a credible, cash-backed sales pipeline to strengthen their case with investors. This model is particularly valuable for capital-intensive technologies where visible demand signals are essential to justify large-scale investment.

“Pre-order agreements can be seen as an instrument to mitigate the “chicken-or-egg” dilemma of showing sales traction before a substantial ramp-up of manufacturing capacity has taken place. Investors acknowledge and value an order book of several (dozen) signed and wired pre-orders. It is an entirely different story to show a stack of signed agreements with money in the bank to diligencing investors—compared to just talking your way through a theoretical sales pipeline that is unconverted.”

Torben Schreiter, Partner at Extantia Capital

Structural offtake solutions

Structural solutions encompass broader ecosystem strategies involving guarantees, commitments, and government involvement to de-risk and catalyze industry growth.

5. Volume guarantees to lower costs

In 2002, the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) set out to reduce the cost of AIDS treatment, which was far beyond reach for the people who needed it most. CHAI needed to negotiate massive price reductions with manufacturers to make these treatments accessible. Manufacturers needed confidence there would be buyers at scale to justify the investments that would be required to cut costs. This wasn’t just a problem for HIV/AIDS. The same market failure existed across many areas of global health, where the commercial risk of scaling production without guaranteed demand kept prices high and access low.

To solve this, CHAI deployed market shaping strategies like volume guarantees—financial tools that promised suppliers a baseline level of demand as a backstop if they met specific conditions, such as hitting price and quality targets. If those volumes weren’t met, donors would step in to cover the gap. In practice, this rarely happened, but guarantees were put in place to provide enough security for manufacturers to invest in large-scale production knowing they wouldn’t be left with unsold inventory. These guarantees have since made it possible to unlock financing, scale manufacturing, and lower prices for many health treatments. By coordinating commitments across donors, governments, and suppliers, CHAI de-risked the market and ensured that if the supply was available, the demand would be there.

This kind of demand assurance and innovative financing is extremely relevant in emerging sectors like alternative proteins, where scaling often stalls because of early demand uncertainty.

6. Advance Market Commitments (AMCs)

In 2022, a consortium of companies including Stripe, Meta, and McKinsey launched Frontier, a $1 billion advance market commitment (AMC) to buy permanent carbon removal and accelerate the development of these technologies with guarantees of future demand. Frontier acts as a “buyer of first resort,” which helps to de-risk investment by guaranteeing a future market for technologies that are not yet fully commercial. To do this, Frontier defines standardised technical and scientific criteria that carbon removal suppliers must meet in order to qualify for purchase agreements, ensuring that funding goes toward high-integrity, scalable solutions.

Applying AMCs directly to alternative proteins is challenging—chiefly because it’s difficult to define standardized criteria for ingredients and products whose functionality varies across different food applications. Still, there are promising pathways. One is to engage institutional foodservice providers—such as universities, hospitals, or corporate cafeterias—as AMC buyers. These buyers purchase in large volumes, have predictable menu cycles, and use ingredients across a range of prepared foods, making them well-positioned to commit to early offtake and send strong demand signals to both ingredient producers and food manufacturers.

Beyond AMCs, there’s a much broader category of “pull funding” which is focused on rewarding outcomes, unlike traditional “push funding” which finances activities like R&D grants. Another example of pull funding is a “prize”, which is a mechanism that seeks to incentivise innovation by tying rewards (which could be funding or even offtake commitments) to specific outcomes. Such “pull” mechanisms can be used to align coalitions of buyers and send credible demand signals to upstream actors in ways that will help spur capital into scale-up.

7. Public procurement

Public procurement isn’t a subsidy; it’s a strategy. During the Cold War, NASA and the U.S. Air Force catalysed the early semiconductor industry by purchasing advanced microchips from the company Fairchild Semiconductor–even buying higher performance chips than immediately needed–to accelerate technological progress, build manufacturing capacity, and drive down costs. Beyond direct offtake, governments can also build ecosystems to de-risk private demand. For example, Taiwan’s government took this approach to grow TSMC, now the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturer, by investing early, developing critical infrastructure like science parks, and, among other strategies, encouraging domestic electronics companies to source locally made chips to stimulate early demand. In both cases, governments strategically de-risked early markets, and supported industry growth in ways that private markets would not have scaled under business-as-usual conditions. Alternative proteins, pivotal for global food security and climate resilience, need the same kind of catalytic public commitment to unlock their full potential.

No offtake, no scale—alternative proteins must secure demand first

Without committed demand, alternative proteins will struggle to reach price parity and mainstream adoption. But in this dynamic industry, traditional offtake solutions are unlikely to cut it. We need alternative protein startups, large corporate buyers, and investors to commit to innovating with corporate partnerships, offtake contracts, pull funding, and public procurement, so that creative offtake can become a pivotal catalyst for meaningful impact and propel alternative proteins to scale.

This is part five in our new Scale-Up series. You may also be interested in part one, exploring key principles for start-ups looking to scale, part two exploring how to find the right target market, part three on building a force-multiplying team, and part four on how to maximise chances of delivering long-term profitability.

Jennifer Morton

Corporate Engagement Manager, GFI APAC

Jennifer works to widen and deepen engagement and partnerships across the alternative protein supply chain.