Alternative protein in the United Kingdom: an ecosystem review

GFI Europe’s analysis maps hotspots of an emerging UK alternative protein ecosystem. By implementing our nine recommendations, policymakers can create the enabling environment needed to help plant-based, fermentation and cultivated meat flourish in the UK.

Read the full report

Green shoots of growth – but more support is essential to develop the ecosystem for alternative protein in the UK

In 2023, the ecosystem for alternative protein in the UK is in its infancy. This report provides a snapshot of its development to date. In particular, we focus on two core pillars: public research and development, and private-sector commercial activity. Our analysis focuses strongly on the spatial dimension of the ecosystem, following the assumption that alternative proteins are likely to be similar to other high-value net zero industries, which are emerging where the UK has significant underlying local and regional capabilities.

We found that:

- Since 2012, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) has invested at least £43 million in R&D specifically for plant-based, fermentation and cultivated meat, seafood, eggs and dairy. Of this funding, almost two-thirds (65%) was allocated between January 2022 and May 2023, suggesting the UK is beginning to seize the opportunity.

- Cultivated meat is a British success story. At least 23 companies are active domestically – who secured more private investment in 2022 than the rest of Europe combined. UKRI has invested more funding in cultivated meat than either plant-based or fermentation, including a new £12 million research hub.

- A diverse range of plant-based, fermentation and cultivated meat research is taking place at British universities, which are also spinning out the alternative protein companies of the future. Much more could be done to tap into the UK’s latent strengths in relevant scientific fields and institutions.

- Precision fermentation is relatively underdeveloped in the UK – both in terms of open-access research and commercialisation. By contrast, the potential of biomass fermentation is already being realised: the North East is home to the largest alternative protein factory in the world – Quorn’s fermentation facility.

- There is a rich diversity in the commercial ecosystem, in terms of business models, geography and scale. We identified at least 138 companies domestically – there are likely to be many more. Plant-based brands are often headquartered in major cities, but much of the economic potential of the plant-based sector is in the food manufacturing capacity growing throughout the regions.

- There are a range of alternative protein hotspots of potential emerging throughout the UK, including Yorkshire and the North East, the Cambridge-Norwich Corridor, and the Golden Triangle. Explore the interactive map below of hotspots across the country to see more.

The UK aspires to lead the world in alternative proteins – here’s how it can by 2030

The UK Government has expressed an ambition to develop and scale-up alternative proteins in Britain, most clearly in its Food Strategy. The remainder of this decade will be crucial to deliver on this ambition and unlock the environmental and societal benefits of plant-based, fermentation-made and cultivated meat, seafood, eggs and dairy.

British entrepreneurs, food producers and scientists need an enabling environment to make new discoveries, grow innovative businesses and produce alternative proteins which are affordable and delicious. Forged by a clear vision and decisive action, this ecosystem can foster the rapid growth of a new green industry in the UK, helping us deliver on national priorities for the climate, economy, food, nature and public health.

Here are our nine policy recommendations to allow the UK to fulfill its potential, grouped under 5 key pillars: political leadership, research and development, infrastructure, regulation and fair competition.

1. Use the forthcoming engineering biology action plan to decisively affirm a cross-government ambition to develop and scale alternative protein production in the UK

The forthcoming engineering biology action plan represents an opportune moment to decisively affirm a cross-government ambition to develop and scale alternative protein production in the UK. This will provide clarity to scientists, investors, businesses and other stakeholders that the UK intends to compete with other world-leading countries in the race to unlock the benefits of protein diversification.

2. Develop a national plan for alternative proteins

A national plan for alternative proteins should set out research priorities, the coordination of public research funding, an infrastructure strategy, fair competitive conditions and the role of agriculture in the transformation.

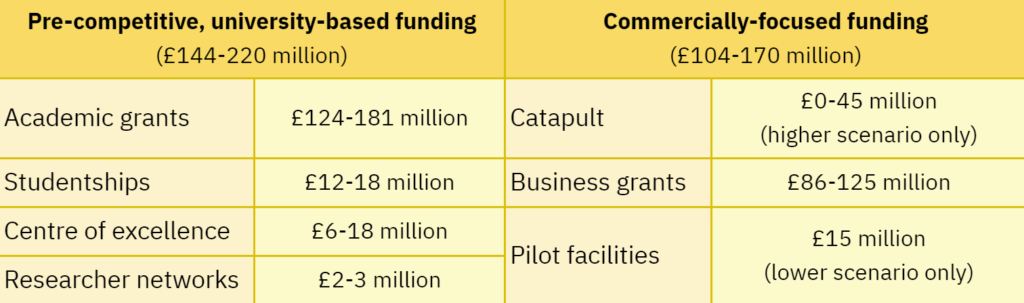

3. Invest between £245-390 million in alternative protein research and development between 2025-2030.

At an absolute minimum, we recommend that between 2025 and 2030, UKRI, DSIT and Defra should together target an average annual spend of £49 million (£245 million total) on public R&D to support plant-based, fermentation-made and cultivated meat, seafood, eggs and dairy.

To truly compete internationally, this should increase to a £78 million average annual spend (£390 million) between 2025 and 2030. To put this in context, our recommended lower and upper scenarios would be equivalent to 2.5% and 4% respectively of BBSRC, EPSRC and Innovate UK’s combined budgets in 2024/25.

4. Conduct or commission a review of alternative protein infrastructure

This should consider both current and future needs, set out a roadmap for what capacity must be built or retrofitted and by when, and outline how the government could target public funding strategically to derisk private investments.

This is crucial to transition the alternative protein sector from venture to patient capital – since the former is not well-suited to expensive, capital-intensive infrastructure investments. A failure to address questions of future infrastructure capacity increases the likelihood that manufacturing will be offshored, reducing the potential benefits to UK food security and economic growth.

5. Implement ‘quick win’ reforms to the UK novel foods regulatory framework

It is no secret that businesses looking to develop cultivated meat and fermentation-made products, as well as some innovative plant-based ingredients and foods, view the current regulatory system as a critical obstacle.

We recommend that the FSA focuses urgently on low-hanging fruit reforms that would improve trust and confidence in the novel foods pre-market authorisation process. Many helpful changes could be made relatively quickly, without legislating.

These include introducing a single point of contact for businesses to engage with the FSA and publishing bespoke, regularly updated dossier-submission guidance to alternative protein companies.

6. Learn from best practices of more innovation-focused regulators, both in the UK and overseas.

The FSA should look to mirror best practices from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulator (MHRA) – both have focused on the unique role regulators play in stimulating innovation.

For example, the FCA has created a ‘regulatory sandbox’, enabling companies to trial innovative concepts with real consumers – something which would be transformative for alternative protein companies. The FSA should also explore whether it could replicate the MHRA’s recent move towards recognising medicines approved by other trusted regulators.

7. Provide the Food Standards Agency with a £30 million increase to its budget at the 2023 Autumn Statement – and ensure its budget increase in real-terms over the rest of the decade.

Having an effective regulatory framework for alternative proteins will be severely limited without an increase in regulatory capacity. The FSA is operating on a frozen budget for the current spending review period (£113 million annually 2022-2025) at a time when inflation (CPI) has hovered between 8-11% – likely leaving the regulator tens of millions of pounds worse off by 2025.

The FSA’s remit has expanded considerably post-Brexit and it now has a clear responsibility to help foster a more sustainable food system. At a minimum, at the 2023 Autumn Statement, the Chancellor should give a one-off £30 million cash injection to the FSA. The next Comprehensive Spending Review should ensure that the FSA’s budget continues to grow in real-terms over the rest of the decade.

8. Remove existing restrictions on the use of dairy terminology – provided adequate qualifiers are used.

Retained EU law means that plant-based foods cannot use common dairy nomenclature like “milk”, “cheese” or “cream” in the labelling and marketing of these products – despite widespread colloquial usage of terms like “plant-based milk” and no robust evidence that consumers are confused by such labelling practices.

An evidence-based, commonsense solution would remove existing restrictions on the use of dairy terminology – provided adequate qualifiers are used. Powers in the Retained EU Law Act could enable ministers to take action on this front.

9. Implement a framework that allows precision fermentation and cultivated meat companies to communicate clearly the nature of their products to consumers.

Government should engage with the evidence base and fill gaps where necessary to build consensus around clear labelling of cultivated meat and precision fermentation-made foods.

It is imperative for food safety reasons alone that the government permits labels that correctly inform consumers that cultivated and precision fermentation-made products contain meat, seafood, egg and/or dairy, including reference to the respective species (e.g. “beef” or “tuna”) to which products serve as alternatives.

Restricting companies to unhelpful and inaccurate terms like “fake” or “in-vitro” will damage the UK’s chances of creating a thriving cultivated meat and precision fermentation sector.

Download the report

Dive into a comprehensive summary of university, supporting institution and company maps, as well as analysis of key policy levers to enable the UK to realise its potential.