Overview

Diversifying Europe’s protein supply is essential if governments are to address global public health challenges such as diet-related ill health, climate change, antimicrobial resistance and pandemic risk.

Increasing the proportion of plant-based foods in our diets is therefore a growing priority for governments – and plant-based meat has a key role to play in this transition. However, while academics and policymakers increasingly recognise the advantages of plant-based meat, many still have questions about its nutritional quality.

Relative to the large body of evidence on the numerous benefits of plant-based whole foods, such as whole grains, beans and vegetables, research into the impact of plant-based meat on health outcomes is still limited. But initial studies suggest swapping conventional meat for plant-based meat could:

- Reduce levels of LDL (bad) cholesterol, and consequently risk of heart disease, the leading cause of death in Europe.

- Reduce risk of bowel cancer, the second largest cause of cancer death in Europe.

- Improve gut health.

- Help maintain a healthy weight.

Therefore, plant-based meat can offer consumers convenient options that are easy to incorporate into their diets as they transition towards more plant-based eating, alongside existing initiatives to improve the availability and accessibility of plant-based whole foods.

How do plant-based meat and conventional meat compare nutritionally?

Like the differences between plain white bread and seeded wholemeal bread, the nutritional makeup of different types of plant-based meat can vary a lot. While there is a lot of variation, surveys of available products can provide average ranges to serve as a yardstick to compare against conventional meat.

Click through the accordion below to see how plant-based and conventional meat compare on key nutrients and against EU guidelines on health claims.

Calories

There is strong evidence that choosing foods with lower calories by weight reduces overall calorie intake. On average, plant-based meat products have similar or fewer calories per 100g than their conventional counterparts.

While a healthy diet is a lot more complicated than simply the energy contained within food, overconsumption of calories is one of the main causes of overweight and obesity, and is therefore an important piece of the puzzle.

For our ancestors, maximising the amount of energy we could extract and either use or store from our food was essential for surviving periods of scarcity. But, in the context of modern-day Europe, overconsumption of calories is a major driver of diet-related ill health.

In the studies surveyed here, plant-based meat generally had similar or fewer calories per 100g. This difference was mostly modest, but for certain categories, particularly meatballs, there was a significant reduction.

Fibre

There is strong evidence that high fibre intake significantly reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and death. High fibre intake is also linked to the promotion of a healthy gut and microbiome, and reduction in inflammation. Plant-based meat is considered a source of fibre, while conventional meat is not. The small amount of fibre in conventional meat products is always derived from added plant-based ingredients.

Fibre is an important part of a healthy diet, and there is strong evidence that higher fibre intake is associated with a reduction in the risk of serious diseases such as coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, pancreatic cancer, and all-cause mortality.47

According to European regulators, foods are considered a source of fibre if they contain at least 3g per 100g, and high in fibre if they have at least 6g per 100g, or 3g per 100 calories. Dietary guidelines in Europe advise consuming 30g of fibre per day, and the majority of people in Europe do not meet these recommendations.

Protein

The evidence on the impact of a high-protein diet on health outcomes is mixed, with different studies finding neutral, positive and negative effects. Plant-based meat comfortably meets the EU definition of high-protein foods, with a percentage of calories from protein similar to that of conventional meat in all categories except fillets.

Nutrition guidelines tend to define protein sources not just in terms of protein content by weight, but the percentage of calories in a foodstuff provided by protein (as opposed to other things like carbohydrates or fat). By this metric, plant-based meat is similar to conventional meat, but it is often slightly lower per 100g.

While this is one of the most common concerns from consumers, most Europeans (including vegetarians and vegans) already consume well above the recommended daily protein intake. Despite this, protein can still be important to the enjoyment of food as it contributes to the feeling of being ‘full’, at least in the short term.

Protein from animals and fungi are ‘complete’ – meaning they contain all of the essential amino acids – but this is not always the case in protein from plants.

Soy, one of the most popular base ingredients for plant-based meat, is a complete protein, as is mycoprotein. Plant-based meats can also use blends of different kinds of protein to achieve an optimal amino acid balance. One common example is the combination of protein from cereals and pulses like wheat and peas.

Bioavailability (how easy it is for the body to use) can also sometimes be lower in plant proteins. However, the processing techniques used to make plant-based meat can offer advantages in bioavailability compared with their raw ingredients.

For more detail on complete proteins and bioavailability see the FAQ section.

Total and saturated fat

Fat is the most energy-dense nutrient, containing nine calories per gram. Diets with lower fat content are therefore likely to result in a lower risk of unhealthy weight gain. There is good evidence that long term reduction of saturated fat intake is associated with a reduced risk of heart attack and stroke. On average, plant-based meats have lower total and saturated fat content than animal products.

The studies found that plant-based meat generally had similar or slightly lower fat content than conventional meat, although plant-based sausages tended to be significantly lower in overall fat. Fat is not inherently bad, and some fat is crucial to a healthy diet – but not all fats are the same.

Whereas overall fat content was slightly lower, plant-based meat contained significantly less saturated fat than conventional meat across all product categories apart from fillets, where the difference was modest. Over half of the conventional meat categories studied were high in saturated fat, while none of the plant-based meat categories were, and many were low in saturated fat.

Research shows that high intake of saturated fat is directly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events (eg, heart attack and stroke) and that replacing it with unsaturated fat (eg, healthy oils, nuts and seeds) is beneficial. The proportion of fats that are saturated in plant-based meat is significantly lower than in conventional meat, with the fat instead coming from plant-based sources.

Sugar

There is good evidence that most people would benefit from reducing their intake of foods high in free and added sugars. On average, both plant-based and conventional meat are low in sugar (less than 5g per 100g).

Although generally there is more sugar in plant-based meat than conventional meat, sugar levels were well within the ‘low sugar’ threshold across all categories and all countries.

Salt

Salt is a significant contributor to diet-related ill health, and there is good evidence that most people would benefit from reducing their salt intake. Salt tends to be similar or higher in plant-based meat compared to conventional meat, but large variation exists across categories and countries.

Some studies have suggested that, in a real-world context, seasoning added during cooking may reduce the difference in salt between meals containing plant-based meat and conventional meat, with a randomised controlled trial led by Stanford University finding no significant difference in salt intake between participants assigned to conventional meat and plant-based meat arms of the trial.

Most European diets contain too much salt. EU guidelines recommend consuming 6g of salt per day or less. There is good evidence linking high salt intake to high blood pressure, which is in turn associated with serious health conditions such as heart disease and stroke. This has led to calls for more attention to be paid to salt added to foods during production.

Variation has been found however. In another recent German study, plant-based meat was found to have similar or less salt than its conventional counterparts across all categories, with plant-based products having nearly half the salt of conventional salami products. Two recent Spanish studies also found plant-based meat on average contained slightly less salt than conventional meat products.

Notably, in further breakdown within the Netherlands study, processed conventional meat had higher salt content on average than plant-based versions, while salt was higher in plant-based versions of unprocessed conventional meat like fillets.

Numbers from the German, Dutch and UK studies are mean values across products, whereas those from the Swedish study are median values. The German study did not look at meatballs or fibre. The Dutch study did not include total fat, and the UK study did not cover strips or sugar.

A more recent German study and two Spanish studies (all from 2023) have also been conducted on this topic but, due to different methodologies and product categorisations, they have not been included in the graphs presented here. These studies were generally consistent with the other findings seen in this section. Please see the appendix of the full report for a summary of their findings.

Where relevant, these graphs show nutrient levels relative to EU guidelines for health claims on food. Thresholds that do not relate to health claims (high fat, high saturated fat, high sugar and high salt) are taken from the UK traffic light system, as there is no standard EU threshold defining this and it is the simplest national guideline of the countries featured in the graphs.

Micronutrients

In the context of protein diversification and the need for increasingly plant-based eating patterns, plant-based meat offers one of the simplest ways to provide key micronutrients that can be lacking in plant-based whole foods.

The way plant-based meat is made can add important nutrients and make others easier for the body to process (bioavailable).

While fortification presents many opportunities, plant-based meat producers wanting to fortify their foods currently face several barriers:

- Fortified food cannot be certified organic (but meat from animals fed the same fortification can be).

- Fortification can be costly.

- There is a growing focus on short ingredient lists, without consideration that some added ingredients such as fortification are beneficial, which may penalise products with higher nutritional value.

Producers may be reluctant to pay more to fortify if it results in a less desirable consumer product, so rates of fortification in plant-based meat vary significantly by country. Of European countries featured in a recent report on the nutritional composition of plant-based meat, fortification rates were by far the highest in the Netherlands (around 75%) where plant-based meat meeting certain nutrition criteria (including fortification) is endorsed by their National Nutrition Centre. This was followed by Belgium (around 50%), Spain (around 40%) and the UK (around 25%). Czechia, Germany, Italy and Poland all had rates below 20% however.

Progress is being made in this regard however: compared to data from a similar study of UK products in 2021, fortification rates there have grown by around 20%, and likewise in the Netherlands significant improvements have been made even since 2023, when only 55% of plant-based meat products were fortified.

Important micronutrients that represent opportunities here are:

- B12. Made by bacteria. Fortification is already the primary source in European diets, but usually via farmed animals fed fortified feed or given injections.

- Iron. Widely available in plants but harder to access in whole plant sources. Iron in some plant-based meat can have similar bioavailability to animal foods.

- Calcium. Conventional meat does not contain calcium, but deficiency is common and bioavailability is limited in plants, so plant-based meat could help meet this need.

- Long-chain omega-3s (EPA and DHA). Made by algae. Seafood is a primary source in European diets today, but deficiency is common. New sources are urgently needed as current production from fish is unsustainable and already insufficient to meet global needs.

- Zinc. With low bioavailability in plants, this is a particular opportunity for plant-based meat made from fungi like mycoprotein.

- Iodine. Found in seaweed and seafood and commonly added as fortification in cows milk. Deficiency is common in Europe, and other fortification such as through salt has seen benefits.

Dietary health in Europe

Given these findings, in particular the higher fibre and lower saturated fat of plant-based meat, substituting conventional for plant-based options could have a significant role to play in improving diets in Europe, helping to reduce overconsumption of red and processed meat to recommended levels.

Alongside low physical activity levels and smoking status, diet is a key predictor of health outcomes across European countries. The 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated that poor diet is responsible for almost one million premature deaths per year in Europe.

Cardiovascular disease (disease of the heart and circulatory system) is one of the largest single causes of illness and death in Europe, accounting for nearly a fifth of ‘disability-adjusted life years’ (DALYs) lost. Poor diet is the largest single driver of cardiovascular disease in Europe, responsible for 40% of deaths, and has a well-established link with the development of other prevalent conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and bowel cancer.

Overconsumption of red and processed meat also plays an outsized role in diet-related ill health. The GBD study found overconsumption of red meat and processed meat were among the top 10 diet-related risk factors for both ill health and death in Europe.

Top 10 drivers of diet-related ill health in Europe

Top 10 drivers of diet-related death in Europe

The role of conventional red and processed meat in disease development is also increasingly recognised by international health authorities such as the World Health Organisation. Many people in Europe eat significantly more than the recommended daily intake of red and processed meat. Research to quantify this impact has estimated that a considerable amount of ill health caused by poor diet can be attributed to overconsumption of red and processed meat.

Red and processed meat are also associated with certain cancers, particularly bowel cancer, while compounds such as resistant starches within plant-based meat are known to reduce bowel cancer risk. Initial studies have also suggested certain plant-based meats may help reduce compounds in the gut linked to these cancers. Bowel cancer is the second most prevalent cancer and the second largest cause of cancer-related death in Europe.

In the United States, the American Cancer Society have announced a partnership with plant-based meat company Beyond Meat to explore the potential of cancer risk reduction using plant-based meat.

Other important public health benefits

Even beyond reducing the harmful overconsumption of red and processed meat, plant-based meat can deliver important public health benefits.

- Combating climate change. Climate change represents one of the biggest threats to public health in the modern era. Conventional animal agriculture represents 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and is the single largest source of methane emissions. Switching to plant-based meat can cut these emissions by 80-90%.

- Countering antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics are the foundation of modern medicine, and overuse is beginning to make common illnesses untreatable and routine operations life-threatening, causing approximately 133,000 deaths per year in Europe. 50% of all antibiotic use in Europe is in animals, contributing to the growth and spread of antibiotic resistance. Plant-based meat production does not require antibiotics.

- Reducing pandemic risk. Using animals for food is a key driver of pandemics, both from exposure to diseases circulating among farmed animals and increased exposure to wild animals resulting from deforestation. Plant-based meat is made without animals and requires significantly less land to produce, minimising both of these core drivers.

- Mitigating food insecurity. War, climate shocks and supply chain vulnerabilities are already driving food shortages – yet Europe currently feeds 45% of all crops it produces to animals. To meet growing global demand for meat while protecting food security, protein diversification is essential.

Frequently asked questions

Is plant-based meat ultra-processed? Does that make it unhealthy?

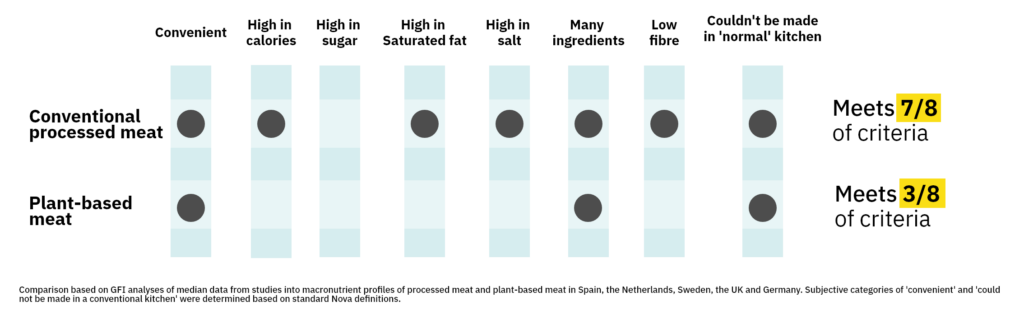

When comparing plant-based meat against the typically used definitions for UPFs, it is clear that they do not neatly fit. Alongside methods used to make them, UPFs are often defined as being high in calories, high in sugar, high in saturated fat and low in fibre – none of which apply to plant-based meat.

Nevertheless, plant-based meat is one of the product categories consumers most associate with being an ultra-processed food (UPF), but research has found that the ultra-processed designation is unlikely to have a large bearing on how ‘healthy’ a food is relative to other better understood factors such as nutrient content (in simple terms, an ultra-processed cake and a home made cake probably have similar health implications).

Comparison based on averages taken from studies into macronutrient profiles of processed meat and plant-based meat in Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK and Germany. Study data did not cover subjective measures such as ‘convenient’ nor ‘couldn’t be made in a normal kitchen’. Categorisations for these two were therefore deduced based on examples used in ultra-processed food definitions.

Comparison based on averages taken from studies into macronutrient profiles of processed meat and plant-based meat in Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK and Germany. Study data did not cover subjective measures such as ‘convenient’ nor ‘couldn’t be made in a normal kitchen’. Categorisations for these two were therefore deduced based on examples used in ultra-processed food definitions.

Plant-based meat is rarely mentioned in landmark studies on UPFs, and in multiple studies breaking down impact by food group, UPFs providing a source of fibre, such as plant-based meat, were associated with reduced health risks. However, ultra-processed conventional meat, which plant-based meat often replaces, makes up a significant proportion of UPFs eaten, and is a subgroup that is frequently associated with particularly negative health outcomes.

While there are some notable issues with the UPF framework as a strictly scientific nutritional metric, as a socio-political framework it clearly captures an alarming ongoing trend towards decreasing diet quality and increasing diet-related ill health in several countries. In this context, however, plant-based meat represents an opportunity rather than an obstacle. With processed conventional meat thought to be a key driver of the adverse outcomes seen in UPF studies, increasing the availability of tasty, affordable plant-based meat products that represent a simple direct swap could be a key lever to facilitate healthier choices and serve as a stepping stone to the greater consumption of plant-based wholefoods.

Why bother? Isn’t eating plant-based whole foods better?

Research has repeatedly found that plant-based whole foods like fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts and whole grains are incredibly good for you. On top of this, many are cheap and readily available. However, this has long been the case, yet overconsumption of meat remains a problem.

Research suggests that groups with the highest consumption of plant-based meat products also tend to eat more plant-based whole foods.

Therefore, while increasing the availability and accessibility of plant-based whole foods is important, alongside this, options like plant-based meat can also play a crucial role as they are easier for consumers to incorporate into their diets as they transition towards more plant-based ways of eating.

Read our recent blog exploring the roles of both wholefoods and plant-based meat

How does plant-based meat affect my microbiome?

There is growing evidence that the gut microbiome could be important in many aspects of health, not only in the gut, but also in our immune systems, blood sugar levels, heart and brain function.

The considerably higher fibre content of plant-based meat compared to conventional meat suggests it may benefit the microbiome. While there is only a small number of studies on this so far, two randomised controlled trials have found benefits for the microbiome associated with replacing conventional meat with plant-based meat.

Doesn’t plant-based meat have lots of ingredients and additives?

Most of the food in supermarkets, including both conventional and plant-based meat products, contain additives. All food additives used in Europe must meet stringent food safety criteria, requiring a large body of high-quality evidence in order to be approved for use.

However, recently some concerns have arisen that certain additives may have previously undiscovered effects. Notably, nitrates, nitrites and nitrosamines used as preservatives in conventional processed meat have been associated with increased risk of bowel cancer.

While some examples like this exist, there is no hard and fast rule as to which additives are helpful (like fortification) and which are harmful, and no evidence that a large number of ingredients is a bad thing in and of itself.

One of the most commonly used additives across all foods, which is often found in plant-based meat, methylcellulose, achieved some notoriety in the United States after it was the subject of an attack ad against plant-based meat, which revolved around the unconventional health metric of being difficult to spell.

While it may have quite a long name, the European Food Safety Authority has in fact approved health claims for methylcellulose. The systematic review they conducted of clinical trial data found it can help blood sugar management and reduce cholesterol in sufficient amounts. There has also been research recommending the addition of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose as an animal fat replacer to improve the nutritional value of conventional meat products.

Do athletes need animal protein to build muscle?

The short answer to this is no. In fact, many high-level athletes, particularly in endurance sports such as cycling and running, follow largely plant-based diets, which research suggests could benefit both cardiovascular safety and performance. Some research suggests that, for elite athletes, consideration of the type of plant protein used could influence their capacity for building muscle.

Advice on specific diets for athletes should be sought from a qualified professional as protein and micronutrient needs are different from the general population.

What about groups with special dietary needs like older adults and those who are pregnant?

It is not in the scope of this page to give specialist health advice, and anyone concerned about making sure they are getting everything they need from their diet should consult a qualified health professional. That said, there is nothing to suggest there would be anything wrong with these people eating plant-based meat as part of a healthy, balanced diet.

What about plant-based milk and eggs?

Due to the size and complexity of this topic, only plant-based meat is reviewed here. A brief summary by Dr Hannah Ritchie of the University of Oxford found that plant-based milk was generally lower than cow’s milk in saturated fat and sugar, as well as protein (with the exception of soy milk). Due to fortification, plant-based milk had comparable or higher levels of key micronutrients, but bioavailability was not explored.

What about the bioavailability of protein and micronutrients in plant-based meat compared to animal based meat?

The bioavailability of a nutrient describes how easy it is for the body to break down and use. Plant sources of protein and micronutrients can be less bioavailable, but certain processing methods used to make plant-based meats improve this. Research suggests fungi and algae protein and micronutrient sources have equivalent bioavailability to animal sources.

The reason for differences in bioavailability between plant sources of protein and other sources like fungi, algae and animals are so-called ‘anti-nutrients’ – chemicals that plants produce as a defence mechanism to reduce the digestibility of the nutrients within them.

The processing techniques used to make plant-based meat can offer advantages in bioavailability compared with their raw ingredients by reducing the presence of these anti-nutrients and enhancing other features that improve bioavailability.

What about protein quality? Does plant-based meat contain complete proteins?

Proteins are made from building blocks called amino acids. Some of these we can make ourselves, and some we must get from the food we eat (known as ‘essential amino acids’). Not all proteins are created equal – and it is important to ensure that across the protein sources someone eats, all essential amino acids are covered.

Protein from animals and fungi are ‘complete’ – meaning they contain all of the essential amino acids – but this is not always the case in protein from plants.

In humans, there are 20 types of amino acid, 11 of which the body can make itself and nine of which need to come from food. Most plant-based protein sources, such as beans or gluten in bread, are not complete protein sources by themselves. However, many popular simple meals like bean stew with bread combine these, and therefore provide all of the essential amino acids.

However, some plant proteins are complete – and these are often the proteins used as the basis for plant-based meat, such as soy. Products made from fungi, like mycoprotein, are also sources of complete protein.

Plant-based meats can also use blends of different kinds of protein to achieve an optimal amino acid balance. One example used is the combination of protein from cereals and pulses. Cereals are usually low in lysine, while pulses tend to be low in cysteine and methionine – but a combination of wheat and pea protein can provide a complete amino acid profile.

So-called ‘incomplete’ proteins are valuable in the diet, and plant proteins as a group have been found to significantly reduce the risk of death from heart disease, whereas no beneficial risk reduction was found in equivalent animal protein intake.

Conclusions and recommendations

Plant-based meat offers people a straightforward swap that can meaningfully improve the quality of their diets without requiring significant behaviour change. Increased adoption can also deliver significant public health benefits, but key opportunities to enhance nutrition and support protein diversification remain.

Governments and funding bodies should invest in advancing research to:

- Develop next-generation plant-based meat products to enable optimisation of nutrient bioavailability and taste.

- Diversify ingredient crops and expand breeding for use in plant-based meat. This will improve the functionality of raw ingredients and nutritional value, reduce the need for processing and additional ingredients, and boost local production.

- Advance novel processing technologies (including fermentation) which can maintain or further boost the nutritional value of raw ingredients.

- Support high-quality trials investigating the health impacts of swapping plant-based for conventional meat to bolster the evidence base underpinning the important role of plant-based meat in public health.

The sector should:

- Better communicate the health benefits of their products to consumers.

- Continue to explore ways to enhance nutritional composition, through approaches such as fortification and salt reduction.

Read the full findings

Read the full report

Read the summary

Alternative protein science

Learn more about our scientific work, including the latest news and additional resources.